I recently found myself reading “Chapter 3 – Constant Frustration and Bursts of Joy” in the book “Coders: The Making of a New Tribe and the Remaking of the World” by Clive Thompson and nodding along saying “Yes! Yes! Yes!” very much like Meg Ryan playing Sally Albright in the restaurant scene in the 1989 movie “When Harry Met Sally”:

the restaurant scene from 'When Harry Met Sally'.

Noooo… just kidding! Since by now I am a senior software developer, I felt more like the senior customer sitting in the next table in that scene and telling myself “I’m having what they are having!”

the restaurant scene from 'When Harry Met Sally'.

Why? Because the chapter perfectly articulates something every software developer experiences sooner or later when building software in a professional context: a considerable part of our time and energy goes into troubleshooting issues/bugs, finding their root cause and implementing fixes or workarounds for them rather than actually writing code for new features.

As a personal example, in one of my previous projects, I implemented a CSV file import feature in a Java-based web application using an external open-source library to handle CSV files. After the feature was implemented, during the QA phase several bugs were found. Great! I fixed them, and eventually we deployed the feature to the LIVE environment. Soon after that, bug reports started coming in from customers that the import was failing. Additionally, there was no clear error message indicating what the problem was.

I looked at the file in the terminal:

$ cat people.csv

name,surname

Sherlock,Holmes

John,WatsonEverything looked fine. I created a unit test to consistently reproduce the issue and be able to iterate quickly. The import logic was failing consistently with that file but working perfectly fine with almost identical files already used in the unit tests I wrote during the implementation. I could not see what the problem was! Having been bitten by similar issues in the past and coincidentally having recently read an article on Hacker News on how to hide messages in emojis and hack the US Treasury, I wondered if the problem was that the tool I was using to inspect the CSV file wasn’t actually showing all the contents of the file.

Suspecting the tool, the magnifying glass I was using to observe the contents of the file was not good enough to uncover the real contents of the file, I asked Claude as if my own personal Dr. Watson “which tool can I use on the command-line to show all the contents of a text file on macOS?” and one of the proposals was hexdump:

$ hexdump -C people.csv

00000000 ef bb bf 6e 61 6d 65 2c 73 75 72 6e 61 6d 65 0a |...name,surname.|

00000010 53 68 65 72 6c 6f 63 6b 2c 48 6f 6c 6d 65 73 0a |Sherlock,Holmes.|

00000020 4a 6f 68 6e 2c 57 61 74 73 6f 6e 0a |John,Watson.|

0000002cWhat were these three dots ... and the corresponding hex values ef bb bf at the beginning of the file? A quick Google search revealed that they are the BOM (Byte Order Mark):

EF BB BFis the Byte Order Mark (BOM) for the UTF-8 character encoding, a special sequence of three bytes placed at the beginning of a text file to tell software that the file is encoded in UTF-8.

In plain English, the BOM is three invisible bytes at the start of the file that say “this is UTF‑8.” If you are wondering what “UTF-8” is, I can highly recommend this Computerphile YouTube video.

Digging a bit more, I found out that when Excel saves a CSV file as UTF-8 in some platforms like Windows, it automatically adds the BOM at the beginning of the file! I also found out that the external library I was using had no support for the BOM. I had found the root cause: I’d been BOMmed (and thoroughly bummed) by Excel!

Unfortunately, I could not change the library since it was used extensively in other parts of the application. I then decided to add logic to check if the BOM was present and remove it before handing it off to the library to process the CSV file.

I share this story not because it’s extraordinary — quite the opposite, it’s completely ordinary. Every developer has plenty of similar stories. Tiny bugs or issues mushroom and end up eating hours or days, and above all, a ton of your mental energy.

What I love about Thompson’s chapter is how he captures similar stories told by well-known developers themselves and at a much larger scale than an enterprise-garden-variety CSV importer.

What follows are excerpts from that chapter interspersed with songs and movie references that came to my mind while reading the book.

What type of personality, what type of psychology, makes someone good at programming? Some traits are the obvious ones. Coders tend to be good at thinking logically, systematically. All day long you’re having to think about if-then statements or ponder wickedly complex ontologies, groups that are subgroups of subgroups. (Philosophy students, it seems, make excellent coders: I met philosophy majors employed at Kickstarter, start-ups, and oodles of other firms.) Coders are curious, relentlessly so, about how things work.

[…]

But if you had to pick the central plank of coder psychology, the one common thread in nearly everyone who gravitates to this weird craft?

It’s a boundless, nigh masochistic ability to endure brutal, grinding frustration.

That’s because even though they’re called “programmers,” when they’re sitting at the keyboard, they’re quite rarely writing new lines of code. What are they actually doing, most of the time? Finding bugs.

What exactly is a bug? A bug is an error in your code, something mistyped or miscreated, that throws a wrench into the flow of a program. They’re often incredibly tiny, picky details. One sunny day in Brooklyn, I met in a café with Rob Spectre, a lightly grizzled coder who whipped out his laptop to show me a snippet of code written in the language Python. It contained, he said, a single fatal bug. This was the code:

stringo = [rsa,rsa1,lorem,text] _output_ = “backdoor.py” _byte_ = (_output_) + “c” if (sys.platform.startswith(“linux”)) if (commands.getoutput(“whoami”)) != “root”: print(“run it as root”) sys.exit() #exitThe bug? It’s on the fourth line. The fourth line is an

ifstatement—if the program detects that (sys.platform.startswith (“linux”))is “true,” it’ll continue on with executing the commands on line five and onward.The thing is, in the language Python, any “if” line has to end with a colon. So line 4 should have been written like this…

if (sys.platform.startswith(“linux”)):That one tiny missing colon breaks the program.

“See, this is what I’m talking about,” Spectre says, slapping his laptop shut with a grimace. “The distance between looking like a genius and looking like an idiot in programming? It’s one character wide.”

In reality, though, bugs are rarely an accident of happenstance. They are the fault of the programmers themselves. The joy and magic of the machine is that it does precisely what you tell it to, but like all magic, it can quickly flip into monkey’s-paw horror: When a coder’s instructions are in error, the machine will obediently commit the error. And when you’re coding, there are a lot of ways to screw up the commands. Perhaps you made a simple typo. Perhaps you didn’t think through the instructions in your algorithm very clearly. Maybe you referred to the variable numberOfCars as NumberOfCars—you screwed up a single capital letter. Or maybe you were writing your code by taking a “library” — a piece of code written by someone else — and incorporating it into your own software, and that code contained some hidden flaw. Or maybe your software has a problem of timing, a “race condition”: The code needs Thing A to take place before Thing B, but for some reason Thing B goes first, and all hell breaks loose. There are literally uncountable ways for errors to occur, particularly as code grows longer and longer and has chunks written by scores of different people, with remote parts of the software communicating with each other in unpredictable ways. In situations like this, the bugs proliferate until they blanket the earth like Moses’s locusts. The truly complex bugs might only emerge after years of coding, when your team suddenly realizes that a mistake they made on the first few weeks of work is now interfering with more recent programming.

As Michael Lopp, the vice president of engineering at Slack, once noted: “You are punished swiftly for obvious errors. You are punished more subtly for the less obvious ones.”

[…]

This explains a lot about the mental style of those who endure in the field. “The default state of everything that you’re working on is fucking broken. Right? Everything is broken,” he says with a laugh. “The type of people who end up being programmers are self-selected by the people who can endure that agony. That’s a special kind of crazy. You’ve got to be a little nuts to do it.”

Nearly every coder who works on big, complex software will tell you a version of this. The dictates of working with ultraprecise machines, so brutally intolerant of error, can wind up rubbing off on the coder.

HAL 9000 to Dr. David Bowman in "2001: Space Odyssey" (1968).

Why can coders be so snippy? Jeff Atwood asks, rhetorically. He thinks it’s because working with computers all day long is like being forced to share an office with a toxic, abusive colleague. “If you go to work and everyone around you is an asshole, you’re going to become like that,” Atwood says. “And the computer is the ultimate asshole. It will fail completely and spectacularly if you make the tiniest errors. ‘I forgot a semicolon.’ Well guess what, your spaceship is a complete ball of fire because you forgot a fucking semicolon.” (He’s not speaking metaphorically here: In one of the most famous bugs in history, NASA was forced to blow up its Mariner 1 spacecraft only minutes after launch when it became clear that a bug was causing it to veer off course and possibly crash in a populated area. The bug itself was caused by a single incorrect character.)

“The computer is a complete asshole. It doesn’t help you out at all,” Atwood explains. Sure, your compiler will spit out an error message when things go wrong, but such messages can be Delphic in their inscrutability. When wrestling with a bug, you are brutally on your own; the computer sits there coolly, paring its nails, waiting for you to express what you want with greater clarity. “The reason a programmer is pedantic,” Atwood says, “is because they work with the ultimate pedant. All this libertarianism, all this ‘meritocracy,’ it comes from the computer. I don’t think it’s actually healthy for people to have that mind-set. It’s an occupational hazard! It’s why you get the stereotype of the computer programmer who’s being as pedantic as a computer. Not everyone is like this. But on average it’s correct.”

[…]

There’s a flip side to dealing with the agonizing precision of code and the grind of constant, bug-ridden failure. When a bug is finally quashed, the sense of accomplishment is electric.

You are now Sherlock Holmes in his moment of cerebral triumph, patiently tracing back the evidence and uncovering the murderer, illuminating the crime scene using nothing but the arc light of your incandescent mind.

Scene from "Sherlock Holmes: Game of Shadows (2011)".

In the past couple of years, having used AI and especially LLMs more and more for my day-to-day work has helped a lot when dealing with the kind of development issues and bugs I described above. So I cannot help but wonder: will the new generation of AI-native coders develop the same kind of tolerance for frustration, or will AI smooth out the daily development work so much that they will no longer need to be so… pedantic.

Is the computer the ultimate asshole? I don’t think so. A computer is just a tool. Maybe even the ultimate tool and with the introduction of AI, this tool is evolving from a very complex but deterministic to a mindbogglingly complex but non-deterministic one.

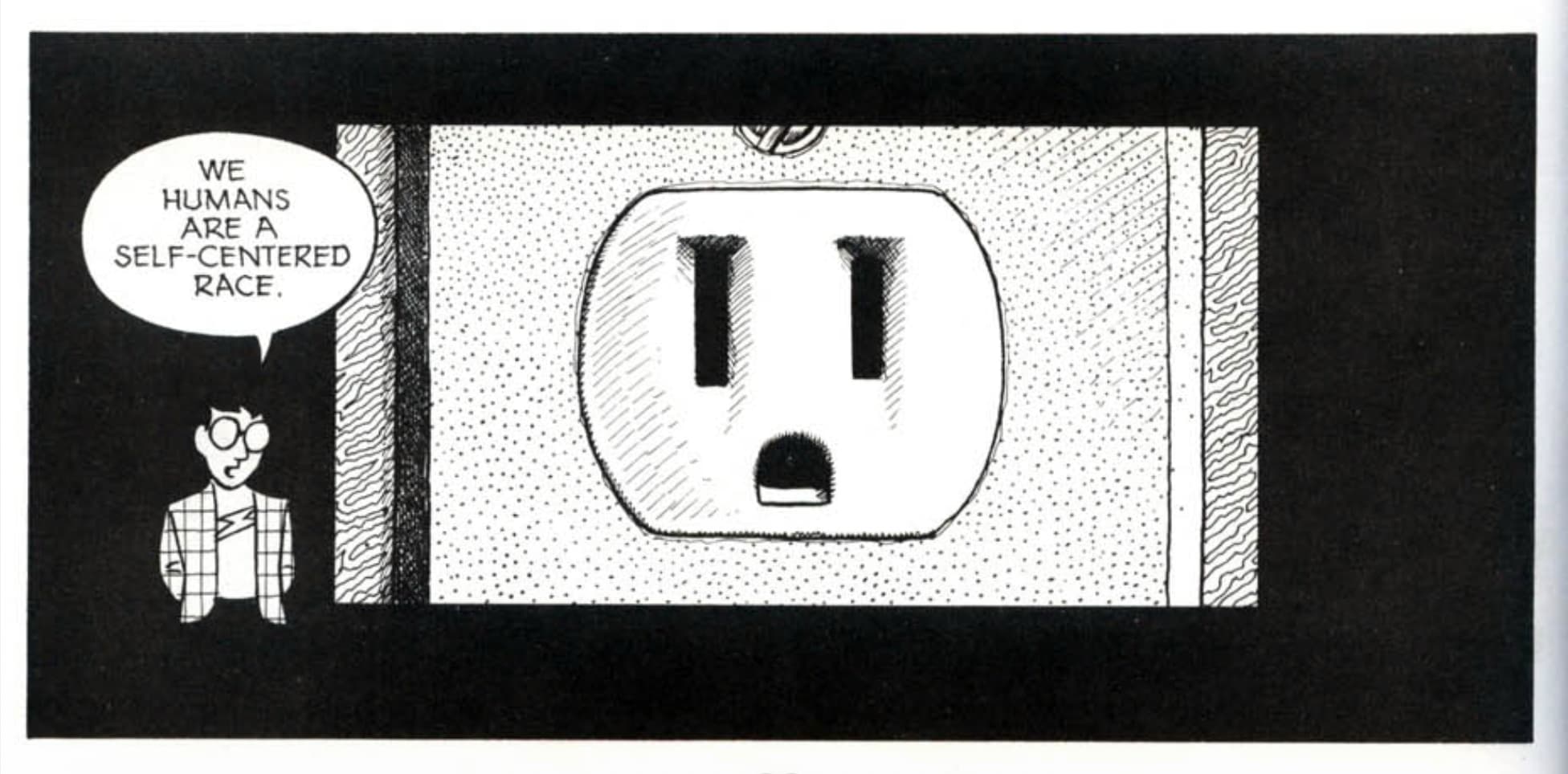

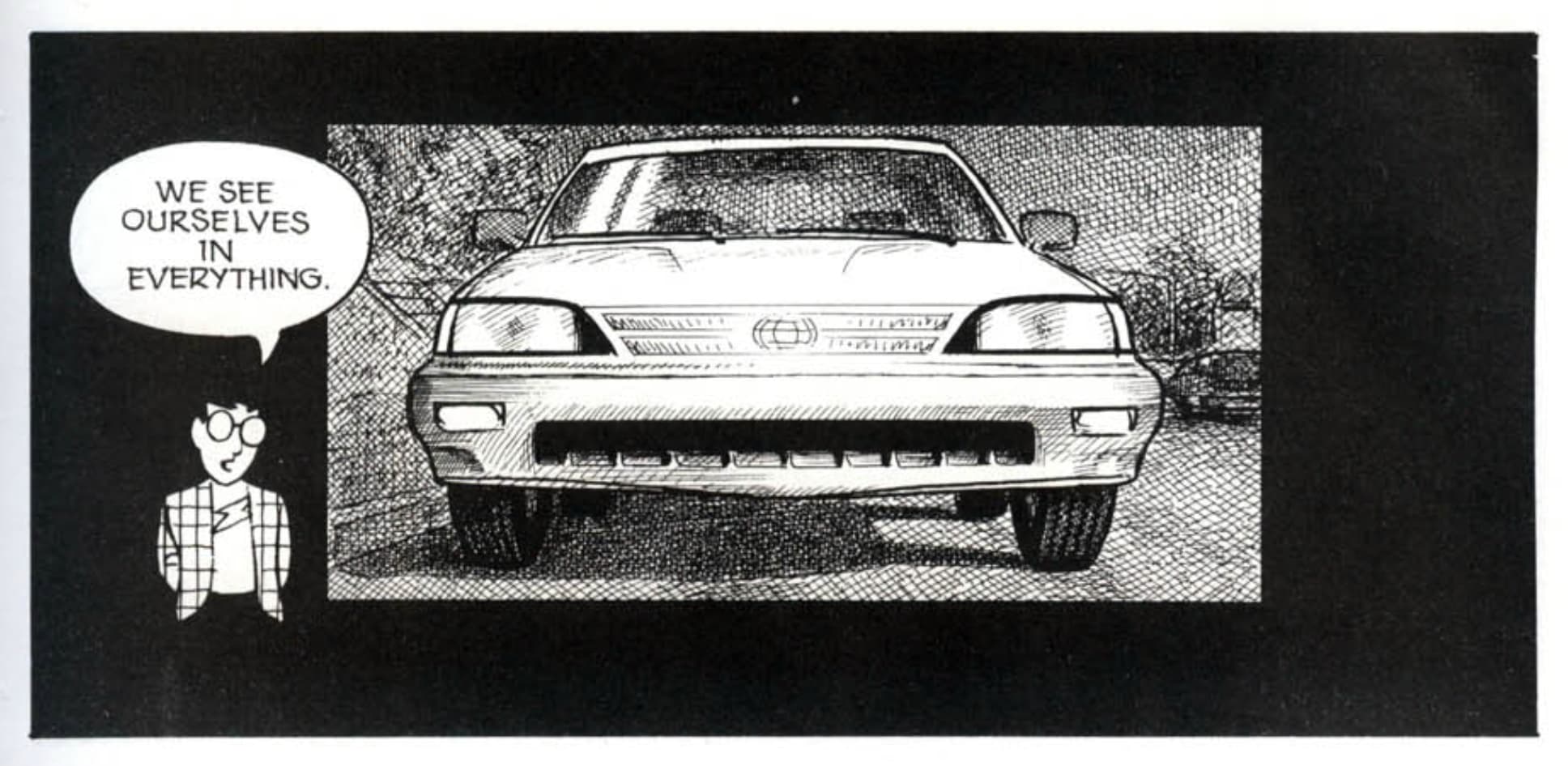

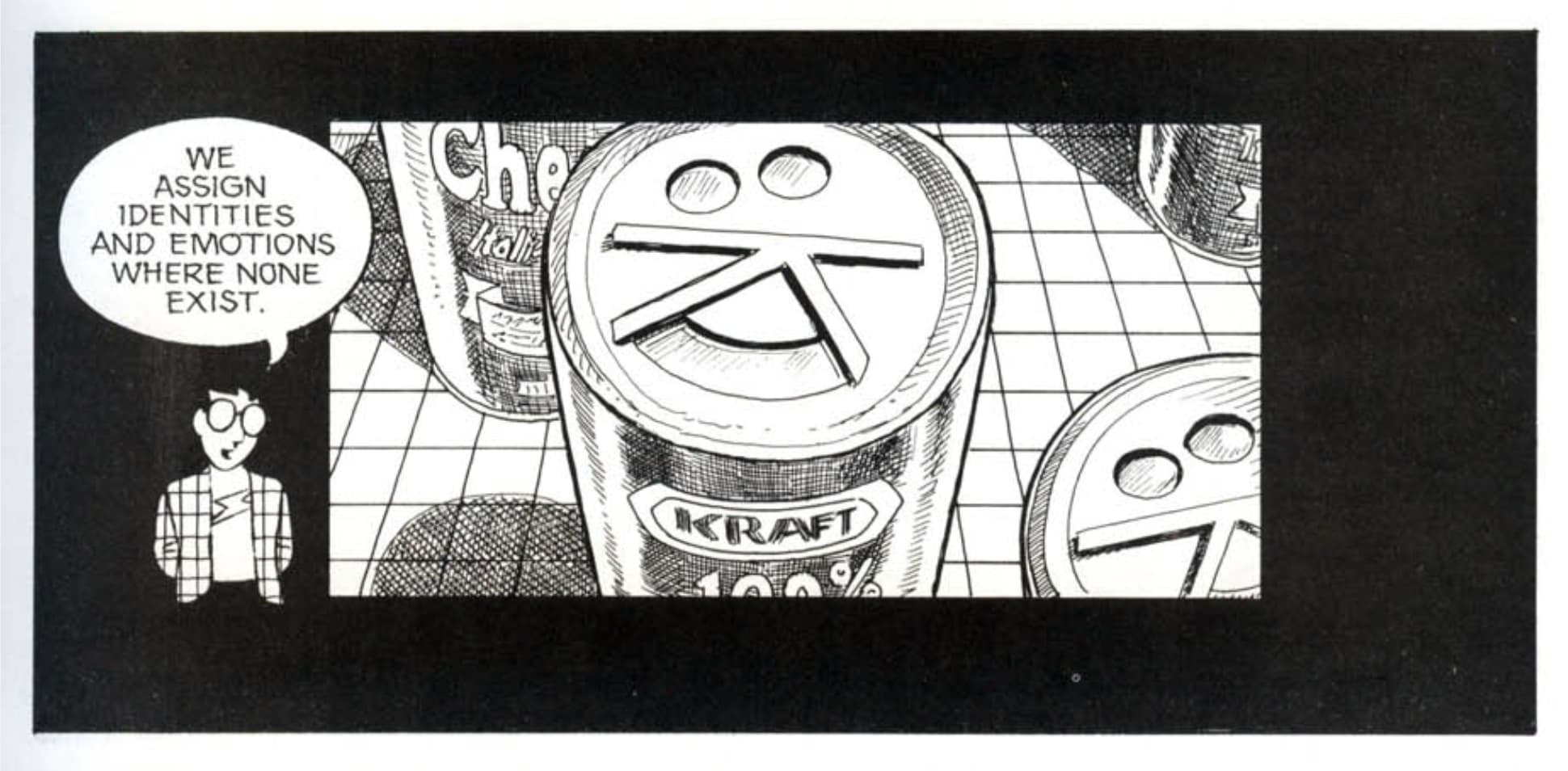

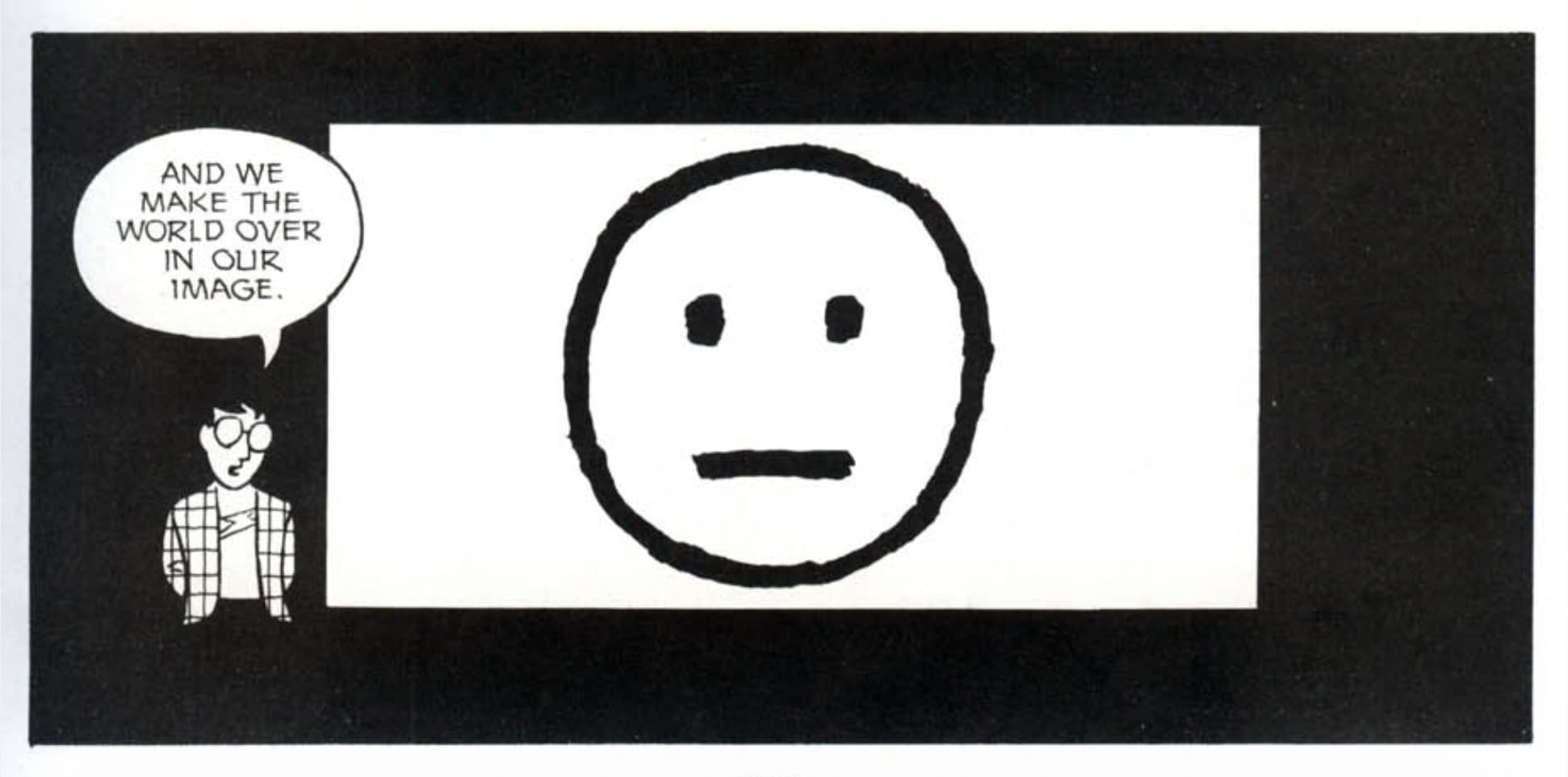

In any case, as Scott McCloud’s says in his book/comic “Understanding Comics”: we humans see ourselves in everything and assign behaviors where none exist.

So it is up to each and every one of us, especially while enduring constant frustration, to make a conscious choice of whether we want to behave like assholes or not.

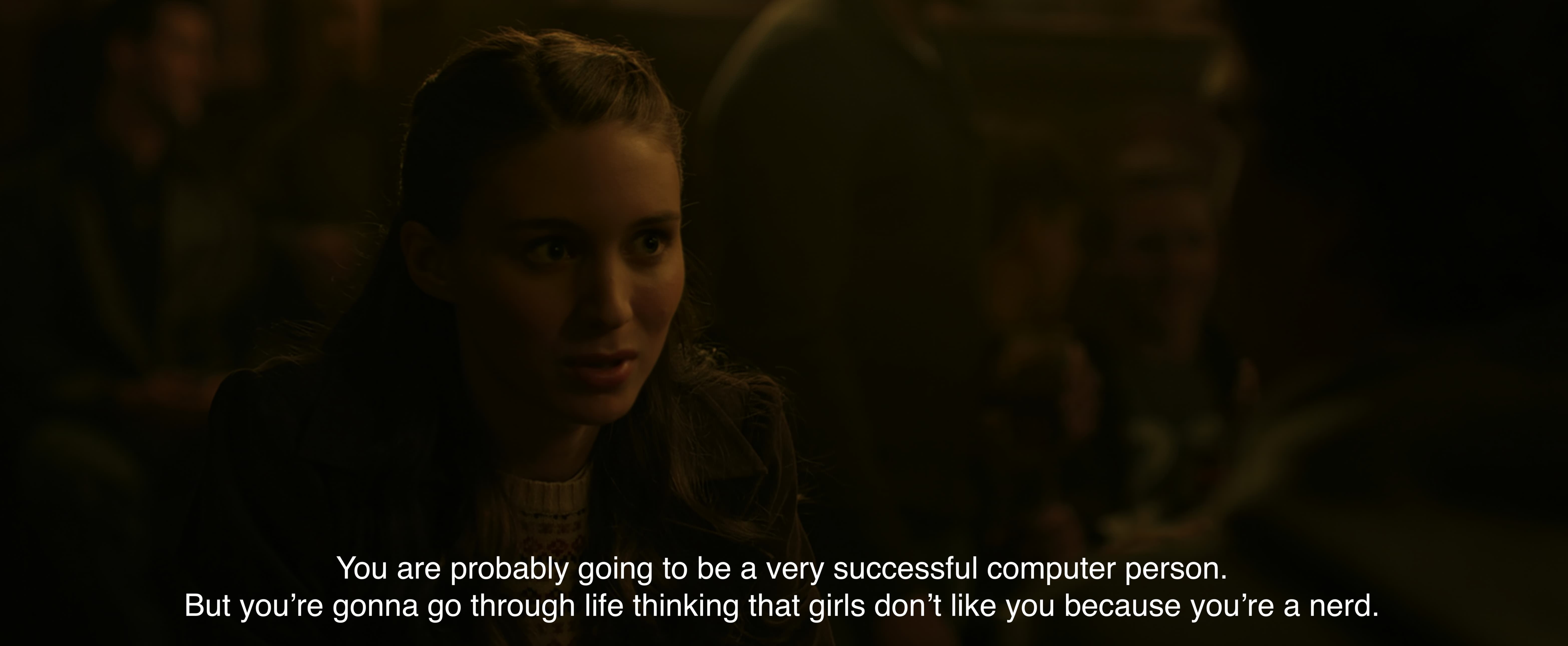

the restaurant scene from "The Social Network".

Even if we decide to interpret the computer’s behavior as that of “the ultimate asshole,” the only behavior we’re truly responsible for is our own. Being a nerd and being an asshole are not the same thing, and we shouldn’t use one as an excuse for the other.

This article was created by me. Claude and Gemini were used to proofread and provide initial feedback.